It has been hard, recently, to escape the bluster surrounding Ofsted, the English school inspectorate. From the circumstances surrounding the appalling and tragic death of Ruth Perry, to the predictable reactions from the DfE and Ofsted, to the everyday anxiety that countless headteachers have to endure because of the sheer inconsistencies that come from trying to cram the totality of a school’s experience into an oversimplified grading system – it is clear that Ofsted in its current form needs a complete review.

It is now becoming more of a problem than those schools it seeks to call to account. Adrian Lyons’ piece in the Guardian yesterday tries to be the voice of moderation: yes, it is important that we don’t overdo the tension, but Ofsted is still essential. Many people will believe him. It is the sort of voice that both Sunak and Starmer might warm to.

But things have gone too far for that.

I was interviewed on Radio Shropshire, about a million years ago, as part of a road safety campaign, and I think I mentioned something about the need for a proper pedestrian crossing on the B5063 between our school and RAF Shawbury, and that the only thing that would actually convince the council to put one in, was if somebody died. Nobody died, so the crossing was not built. Quick look at Google Maps – still no crossing, although less need now as the school closed…

But this time, somebody has died.

From the shame of being called an inadequate leader by a body that should know better than to use foolish labels. The labels, by the way, are invidious, as much for schools as for children. Whilst there is an argument for evaluation of schools, the labelling is not an effective means of doing that. It has been known for a long time that variation within schools is greater than the variation between schools – in a whole host of areas, including teacher quality. How could it be otherwise? If schools are employing new teachers all the time (and there are myriad reasons for the churn in teacher recruitment and retention) of course that within-school variation will be maintained.

The rise of Ofsted came from the same neoliberal root that gave rise to the National Curriculum and league tables in the 1988 Education Reform Act. There was a longing amongst those on the radical right to commodify and marketise education in the same way that everything else was being commodified by the three Thatcher governments. The use to which Ofsted was to be put was clear from the start, in retrospect: to separate out the good and the bad schools and, along with league tables, to create a school market that gave parents (as consumers or customers) choice over where to send their children.

In just that statement, it is worth pointing out that at a stroke, the value of school to a community, its cohesive properties as belonging to a place, and its historical import as a place of memories and tradition, were destroyed or seriously undermined. Moreover, those with cars, money and the right kind of materialist ambition, could move children around in response to these gradings and league tables. This was not an unfortunate side effect of the 1988 Education Reform Act. If it had been, then the governments of Blair, Cameron, May, Johnson, Truss (remember her?) and Sunak, would not have indulged an anti-democratic assault on local authorities, pushed the grammar school agenda, and introduced academies. No, it was deliberate from the start, and if Ofsted had some redeeming features it was because of the professional and thoughtful work done by those who entered it to serve education.

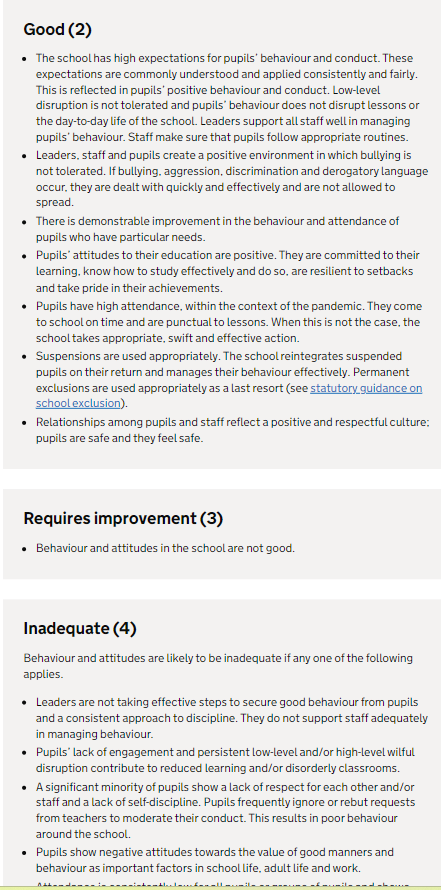

Ofsted, in its early iterations, was a serious-minded institution. It looked at a variety of outcomes, across a range of subjects, and had a degree of nuance that for those inspections I remember from 1999, 2002 and 2003 (the first when I was a class teacher; the latter two were when I was a head) was both interesting and supportive. Reports were upwards of 40 pages long, and contained abundant information that could be used for school improvement. In 2004, everything changed, the four-grade system appeared (it is actually a three-grade system, because the descriptor for ‘requires improvement’ is defined wholly with respect to the descriptor for good – see the excerpt, left), and the concept of being satisfactory was removed.

Now, from evidence and much anecdote, it is on its way to being a disgrace, and needs replacing. It might not have descended to the depths of the Metropolitan Police, but as a government agency, I think it is now doing more harm than good. Worse, it has been part of a long-standing agenda from the last six governments that distrusts school leaders, distrusts local democratic accountability and which has fed to parents and other stakeholders a simple but destructive language of gradings that is both meaningless and a mental stronghold at the same time. The word ‘outstanding’ has both garnered meaning to itself through the press and the affirmation of government ministers over 20 years, but at the same time has lost its meaning as previously ‘outstanding’ schools are suddenly judged less than that, with little obvious change in practice or quality. Those who have studied the discourse of Ofsted from the perspective of critical discourse analysis (CDA) see the problem getting worse, and not better. Zahid Naz, from Canterbury Christ Church University, puts it like this:

The Ofsted inspection paradigm…could be viewed as a specific technology of power pertaining to an economic rationality that seeks disciplined institutions that produce disciplined and responsible consumers for a cost–transaction society.

In other words, Ofsted feeds the beast of parents wanting to know how good their child’s school is by portraying the rightness of their judgments as a technological judgment – hence the introduction of AI algorithms as predictors – and nothing to do with the vagaries of individual inspectors.

And the problem is inherent, and beyond fixing. Because of its roots in the neoliberal Education Reform Act, Ofsted was conceived as a marketising force. We need to get rid of it, but at the same time, we need to find a way of supporting schools to improve, to make sure children are safe, and to help those working in schools to look forward to the evaluation of their considerable knowledge, skills and understanding as a common good.

Our fundamental problem is because of the existence of Ofsted, we have failed as a society to invent anything better. There have been attempts – organisations like Challenge Partners have done a wonderful work for schools – as well as many ‘moderating’ arrangements between schools locally. But whilst Ofsted exists, it will always narrow the scope of judgment because of the position that the state has placed it in the minds of parents, governors, local authorities (who may not like it, but have to respond as if the judgments are sound) and local businesses.

Ofsted has to be got rid of, in order to clear the field so we can invent something better. It remains to be seen whether the first serious political alternative, that proposed by the Labour Party, will root its replacement in a better philosophy, and show the care, affection and appreciation that our society’s schools deserve. Early signs were promising. More recent ones, less so.

One of the things that has horrified me about press statements by politicians and OFSTED since Ruth Perry’s death is the complete lack of reference to the interests and concerns of the teaching profession. They only refer to parents and politics. I do not consider this accidental. Many years ago, teachers replaced civil servants as the political footballs du jour. (I noticed, as a former civil servant.) Today I read this horrendous quote in the i paper from a former headteacher and OFSTED inspector:

“My experience as an inspector was mixed, to put it mildly. On one inspection, I reported to a senior colleague that the headteacher had physically collapsed with indications of stress. He responded curtly that it was “for the school to deal with” and turned back to his laptop. I then quit inspection work – on moral grounds.”

https://www.independent.co.uk/voices/ofsted-inspection-school-teachers-ruth-perry-b2305237.html